Despite rapid advances in precision medicine, Indigenous populations remain largely invisible in genomic datasets. In this blog, Manuel Corpas shares his journey working with Peru’s remarkable genetic diversity — and why including underrepresented populations is critical for a fairer, more effective future in healthcare. From the devastation of the Inca Empire to today’s genomic frontiers, this is a story of resilience, discovery, and hope.

In recent years, my research journey has taken an unexpected and deeply meaningful turn. Initially, my focus was on the technical side of genomics: how to manage and interpret the overwhelming flood of data we now generate every day. But as the field of genomic medicine evolved, it became impossible to ignore a much larger issue — one that is less about technology and more about fairness. While precision medicine has made remarkable strides, most of its benefits are concentrated in populations of European descent. The rest of the world, including vast swathes of Latin America, remains largely invisible in the genomic datasets that drive medical breakthroughs.

This realisation changed the direction of my work. I made it my mission to bridge this gap by helping to bring the advances in genomics developed in countries like the United Kingdom — a global leader in applying genomics to clinical care — to Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America. Peru, in particular, quickly captured my attention. With its breathtaking geographic diversity — from coastal deserts to towering Andean peaks to the vast Amazon rainforest — Peru has nurtured an extraordinary range of human adaptations over millennia. Its people, descended from ancient civilisations like the Inca Empire, carry genetic signatures shaped by centuries of resilience and survival.

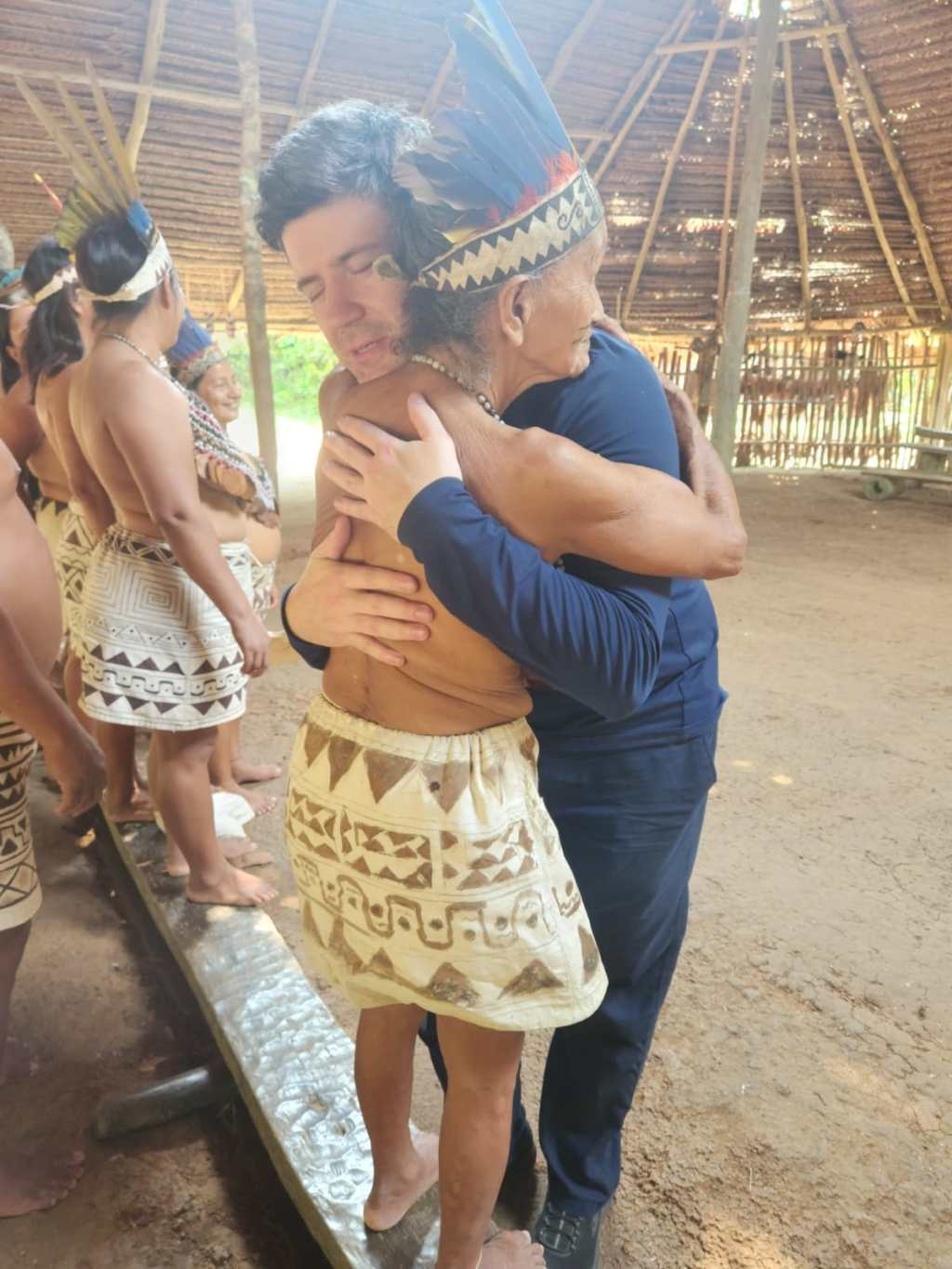

Before diving deeper into this research, I want to be clear about the principles that guide my work. Respect for Indigenous peoples and their traditions is non-negotiable. I conduct my research with the utmost sensitivity, recognising the cultural, spiritual, and historical significance embedded in the genomes I study. I also firmly reject “genetic colonialism,” a practice where scientists extract data from Indigenous communities without offering any benefits in return. My work is committed to ethical partnerships, ensuring that any insights gained are shared with and beneficial to the communities themselves. Finally, I know that centuries of exploitation have left deep scars, and trust in science must be earned, not assumed. Transparency, collaboration, and real dialogue are the cornerstones of my approach.

Peru’s Indigenous diversity is extraordinary. Despite its smaller size compared to countries like Brazil, Peru has the largest Indigenous population in South America. Many of these groups, especially in the Amazon, have remained relatively isolated, preserving genetic lineages that differ as much from one another as Europeans do from East Asians. Understanding these differences is not simply a matter of historical curiosity. It is key to building a future where personalised medicine truly works for everyone, not just for those who happen to be well-represented in current databases.

The need for better representation in genomic research is not just an academic issue. It is also visible here in London, where the Latin American diaspora has grown by over 400% in the last two decades. Yet many Latin Americans here suffer exploitation and invisibility, working in precarious conditions with little recognition. Whether in Peru or in London, increasing visibility — in science, healthcare, and society — is critical for justice and equity.

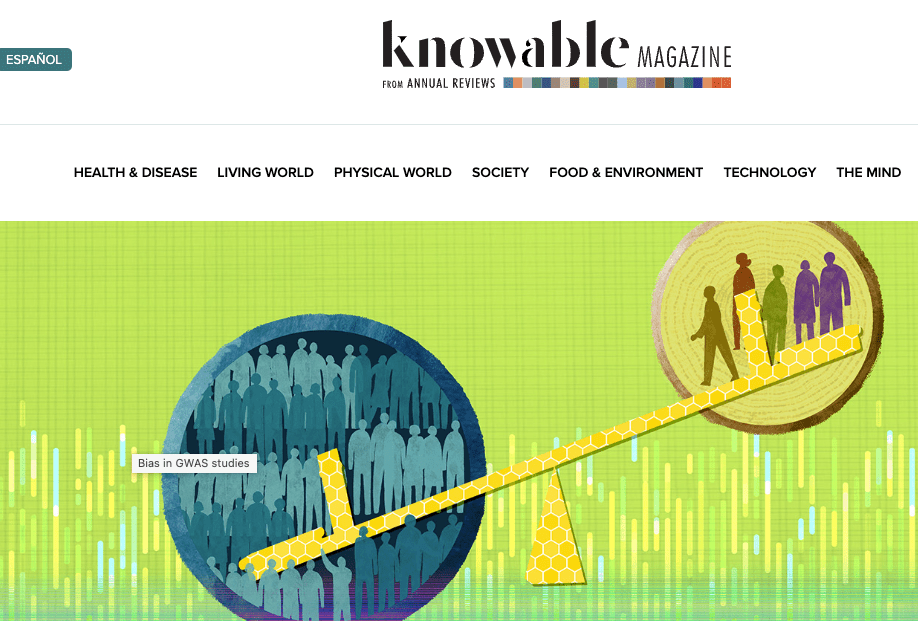

Unfortunately, the problem of underrepresentation in genomic data is stark. Native American genomes are almost absent from the reference datasets that drive much of global medical research. Genome-wide association studies, the workhorses of modern human genetics, are based 95% on European populations. Without diversity, the risk predictions and treatments derived from these studies are incomplete at best, and dangerously misleading at worst. Precision medicine promises to tailor healthcare to the individual — but it cannot fulfil that promise if it only “sees” a narrow slice of humanity.

Including diverse populations in genomic research isn’t just ethically necessary — it makes the science better. It reduces biases, improves the accuracy of genetic models, and reveals new insights into disease mechanisms that might otherwise be missed. Diversity in genomics isn’t about ticking a box; it’s about building a richer, more truthful understanding of what it means to be human.

The story of Indigenous Latin America is written in our DNA. Around 23,000 years ago, the ancestors of Native Americans separated from East Asians and began their long journey into the Americas. In South America, the formidable geography carved their descendants into three major branches: those who stayed along the Amazon basin, those who scaled the Andean mountains, and those who remained on the coast. For thousands of years, these groups lived largely isolated lives, developing unique genetic adaptations to their environments.

This isolation persisted until a tragic turning point: the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in 1532. At the time, the Inca Empire was at its zenith, home to an estimated 16 million people. Within a few decades, that number plummeted to fewer than two million, not primarily due to violence, but because of European diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis, against which Indigenous populations had no immunity. This catastrophic collapse left a profound genetic legacy that still echoes today.

In collaboration with Dr. Heinner Guio and colleagues in Peru, I have been privileged to work on the Peruvian Genome Project, a pioneering effort to capture the genetic diversity of Peru’s Indigenous populations. We collected around 150 full genome sequences and over 850 targeted genotyping samples from 30 locations across the country. Although small compared to global biobanks, the diversity captured in these samples is remarkable. When we analysed the data, we found that the genetic clustering mirrored Peru’s geography almost perfectly: Amazonian, Andean, and coastal populations each formed distinct branches, with some, like the Uros people who live on floating islands on Lake Titicaca, displaying particularly unique genetic signatures.

The findings are both fascinating and clinically important. We discovered unique genetic variants associated with immune system function and skeletal traits. There is evidence suggesting that Indigenous Peruvians have specific adaptations related to infectious disease resistance — adaptations that could be the lingering legacy of the epidemics that devastated their ancestors. These insights could help explain why Peru, tragically, had one of the world’s highest COVID-19 mortality rates. They also open the door to better, more targeted treatments and vaccines for Indigenous and mixed-ancestry populations across the Americas.

In the end, the genome of the Inca descendants tells a story of migration, survival, loss, and resilience. It also holds the key to a more inclusive and equitable future for genomic medicine. Expanding who we study expands what we know — and it expands who we can help. Science should not leave anyone behind. And in listening to the genomes of the forgotten, we might just find the answers the whole world needs.

Leave a comment