By Dr Manuel Corpas

Precision medicine is built on a contradiction. The field promises individualised care calibrated to each person’s biology, yet its foundations rest on data representing a fraction of humanity. After two decades at the intersection of genomics, artificial intelligence, and global health, I have reached a conclusion that the field must confront directly:

You cannot have precision medicine with partial data. And today, our data is profoundly partial.

This is not a diversity problem to be managed. It is a scientific validity problem that undermines the entire enterprise. Genomic medicine is making 100% claims on 80% foundations.

The Promise and the Fracture

For most of medical history, treatment followed population averages. Clinicians asked: What works for most people? The answer was imprecise at best and harmful at worst.

Consider the evidence: for every person helped by a top-10 prescribed drug in the United States, between three and twenty-four people fail to benefit—some experiencing adverse reactions. This is what happens when treatments are calibrated to a mythical “average patient” who does not exist.

Genomics offered a different question: What works for this person? The cost of sequencing a human genome collapsed from $100 million in 2001 to under $1,000 today—a trajectory that outpaced Moore’s Law. Medicine could finally become personal.

But this promise rests on a fragile assumption: that the underlying data represents the full diversity of human biology. It does not.

The Data Fracture at the Centre of Precision Medicine

Here is the defining statistic of contemporary genomic medicine: approximately 80–86% of all genome-wide association study (GWAS) data derives from individuals of European ancestry. Europeans constitute roughly 16% of the global population.

This imbalance is not incidental. It is structural, and it cascades through every layer of the precision medicine pipeline.

Reference genomes were constructed predominantly from European donors. Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS) are substantially more common in non-European ancestries, precisely because those populations lack adequate representation in the databases used to interpret clinical meaning. Polygenic risk scores—the most promising tools for predicting complex disease—show predictive accuracy that decays linearly with genetic distance from European training populations. Drug response predictions, calibrated on narrow populations, miscalculate for large regions of the world. And AI models, trained on biased data, amplify these distortions at scale.

This is not merely an equity concern. It is a scientific validity problem. When narrow data is used to build universal models, the science fails on its own terms.

Beyond Single Genes: The Polygenic Reality

Before the genomic era, Mendelian disorders—single-gene conditions—dominated the field. These remain important but rare.

The vast majority of the global disease burden—diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, cancer—is polygenic, involving hundreds or thousands of variants interacting with environment and lifestyle. This reality complicates interpretation substantially: small genetic effects accumulate; environment modulates risk; no variant determines destiny; and critically, all of this depends on the population in which the model was trained.

Precision medicine constructed on narrow ancestry cannot deliver precision for global populations. What we have instead is statistical inference masquerading as clinical truth—confident predictions that work well for some populations and fail systematically for others.

Why Studying Peru Illuminates Global Biology

My research centres on Peru, a country whose genomic and environmental diversity challenges the assumptions embedded in current databases.

Peru comprises over 55 Indigenous populations, deep Amazonian ancestries, and high-altitude groups who have lived above 3,000–4,000 metres for millennia. Roughly 30% of the population resides at extreme altitude, where oxygen availability drops to approximately 60% of sea-level concentrations. Over thousands of years, these conditions have reshaped immune pathways, cardiovascular responses, and metabolic processes in ways absent from global genomic resources.

The findings are instructive: high-altitude immunity operates through distinct pathways compared to low-altitude populations; protective variants in one environment can become vulnerabilities in another; drug metabolism patterns diverge significantly from European-centred assumptions.

This work is not only about Peru. It reveals biological mechanisms that would remain invisible if the genomic lens remained Eurocentric. The diversity that has been excluded from genomic research is precisely where novel scientific insights reside.

Measuring What Matters: The HEIM Framework

Addressing these structural imbalances requires tools that do not yet exist. To this end, my team is developing the Health Equity Informative Markers (HEIM) framework, designed to quantify the equity and representativeness of genomic datasets, establish diversity standards, embed data sovereignty and benefit-sharing principles, provide equity metrics for AI models, and translate representation directly into clinical guidelines.

The field speaks frequently about diversity. It rarely measures it. Without quantification, diversity remains aspiration rather than methodology. HEIM is designed to change that equation—to move equity from rhetoric to rigour.

The Paradox Stated Plainly

Precision medicine is being constructed on incomplete data while making universal claims. The field asserts individualised accuracy while ignoring the populations for whom that accuracy does not hold.

The evidence of this contradiction is already visible. Polygenic risk scores fail when applied to African, Latin American, or South Asian populations. Variant interpretation becomes unreliable outside European reference frames. Drug dosing guidelines misfire in Indigenous communities. Clinical tools optimised for European ancestry may work adequately for that population—but they do not generalise.

The global spread of precision medicine, absent correction, risks deepening the very inequities it claims to address. We cannot build equitable healthcare on inequitable foundations.

Toward Precision Medicine That Works Globally

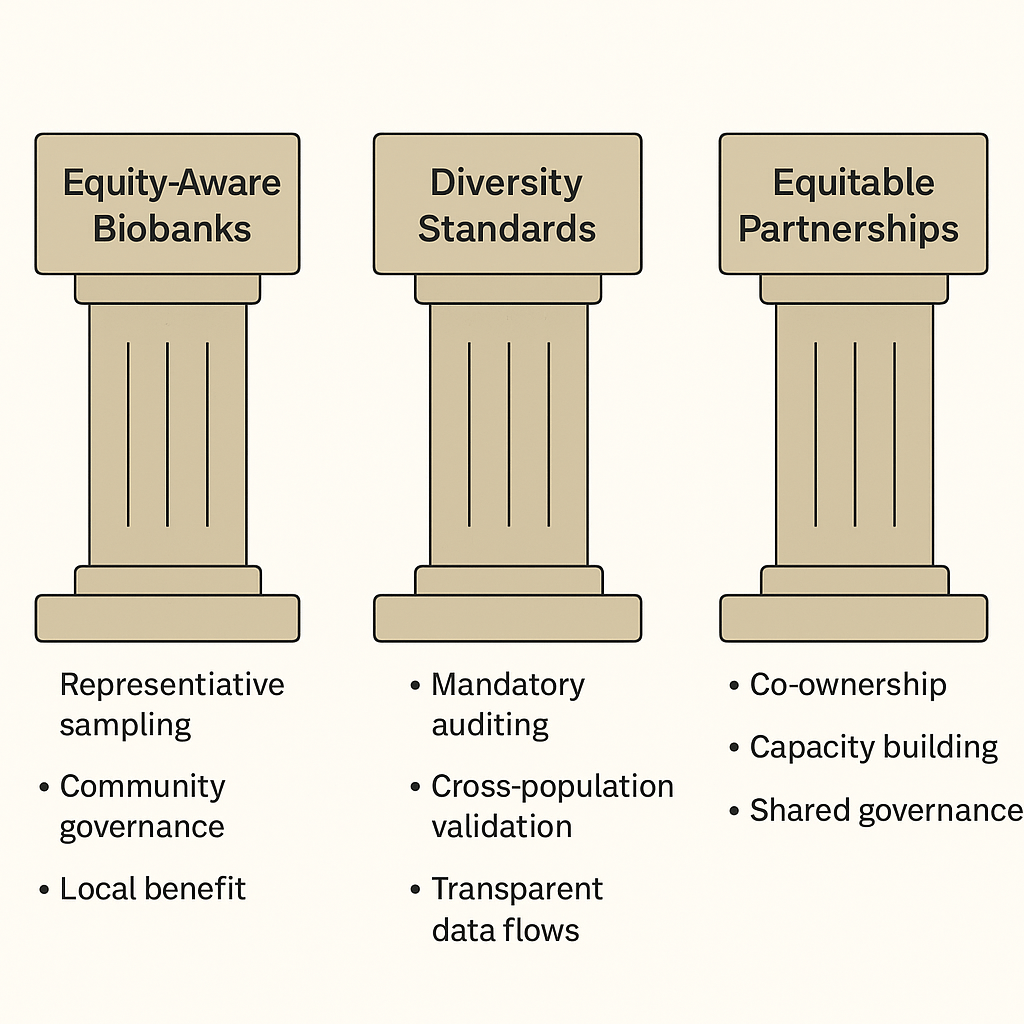

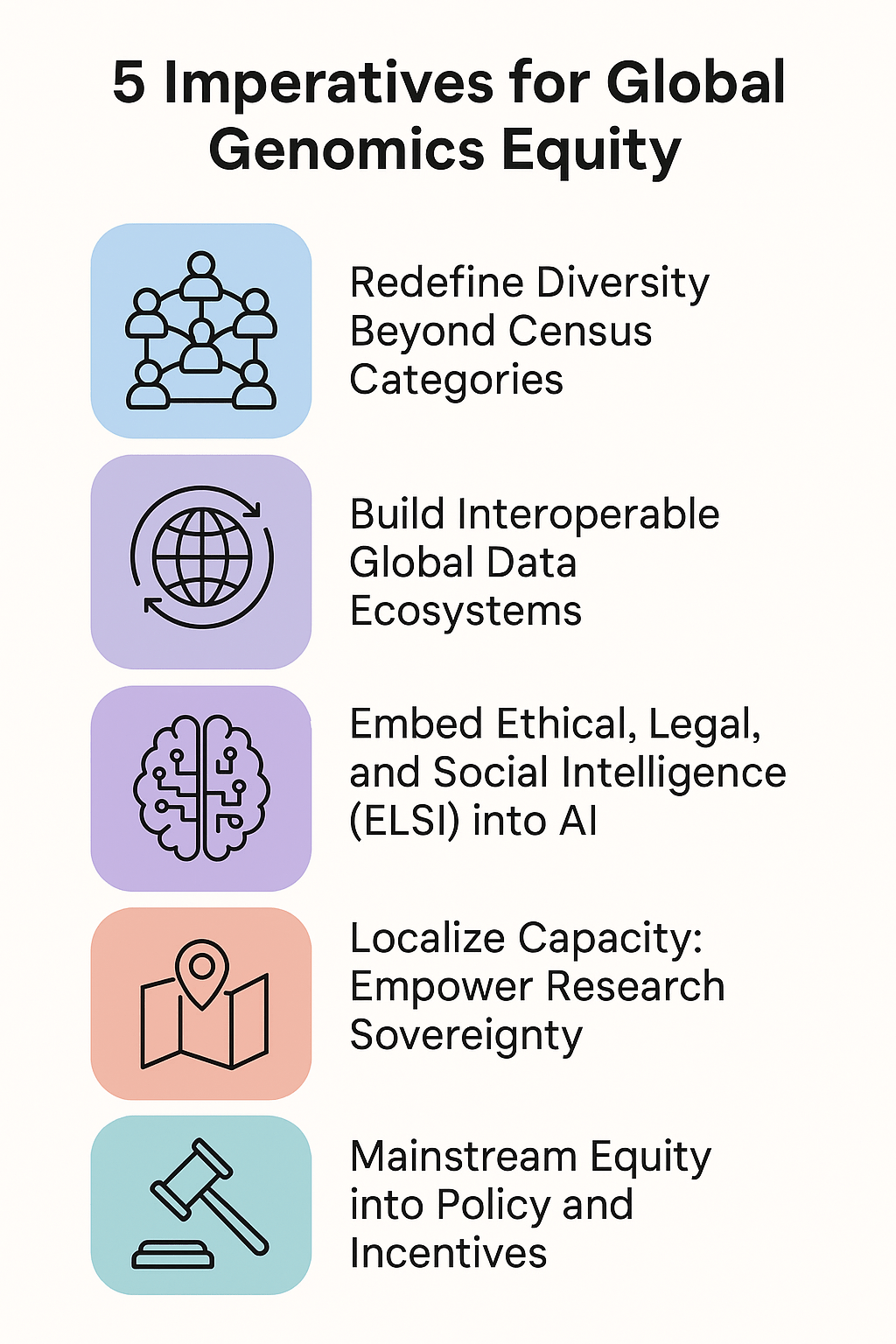

Delivering on the original promise of precision medicine requires a fundamental reorientation of practice.

First, representation in genomic research must expand—not as a compliance exercise, but as core scientific methodology. Populations currently underrepresented in databases are not supplementary to science; they are essential to it. The variants, adaptations, and disease mechanisms present in these populations hold keys to understanding human biology that Eurocentric data cannot provide.

Second, AI models must be designed and validated to work across populations, not merely tested on convenient cohorts and then deployed globally. Technical solutions exist; the barrier is institutional will.

Third, data sovereignty must become standard practice. Communities contributing genomic data should hold governance rights over that data. The extractive model—where data flows from the Global South to Northern institutions without reciprocal benefit—is scientifically limiting and ethically untenable.

Fourth, collaboration must replace extraction. Underrepresented populations should be partners in research design, interpretation, and benefit, not subjects from whom data is harvested.

Fifth, clinicians and scientists must be educated that genetic risk is probabilistic, not deterministic, and that the confidence intervals widen dramatically when tools are applied outside their training populations.

Precision medicine cannot remain a privilege available to those who fit the reference genome. It must become infrastructure that works for everyone.

The Path Forward

The potential of genomic medicine remains substantial. But that potential cannot be realised on fractured foundations. The decisions the field makes now will shape healthcare for the next century.

My work—and increasingly, our collective work—must ensure that precision medicine serves all of humanity, not merely those whose ancestors happened to be recruited into early studies. If we want the future of medicine to be truly precise, it must first become truly equitable.

The science demands it. The ethics require it. And the populations currently excluded deserve nothing less.

Dr Manuel Corpas is a Senior Lecturer in Genomics, AI, and Data Science at the University of Westminster, focused on advancing equitable genomics for global health.

Leave a comment